A few years ago, I started an accidental, slow, and now intentional process of remembering who I am when not producing for others. To reclaim my voice not as a teacher or a brand, but as a person. To write from what’s really going on inside, in a way that occasionally afflicts you with what Brené Brown calls a “vulnerability hangover.”

It can be difficult to create for yourself when your voice has been shaped by “what works.” Creating with metrics and outcomes in mind makes it hard to say anything just because you want to.

I’ve lived in the internet marketing and personal branding world for the past decade, where “adding value” is a tenet.

It can also be a trap.

I dislike the phrase “adding value.” I’ve never once described a good friend that way. Sure, a good friend is helpful, inspiring, comforting. But a good friend is also frustrating. They make you think, call you out, egg you on, and push your boundaries. In other words, a good friend just helps you be your real self.

So, I’ve committed to writing as a truer friend to myself.

If anyone happens to read along, truth offers more value than tips, anyway.

***

Recently I successfully lived another year. Birthdays have always made me reflective but this one was the first since my father passed, a complex figure in my life.

We never got along and there were wild things aplenty: a near-death experience in childhood when he accidentally ran me over with the car, domestic violence, visiting him in jail.

As the years passed, the question of what shaped him became harder to ignore. In my early 20s, I was fascinated by psychology and regret not taking more classes in college. I wanted to understand what in the world was going on with my father, how he affected me, and how to make sure I wouldn’t turn out like him.

With time came compassion and understanding. No, I don’t believe he “did his best,” a throwaway line too often used to avoid the reality that there’s usually more a person could do. They just don’t. So I accepted what he did (or didn’t) and chose to love him anyway. As a verb. As an action.

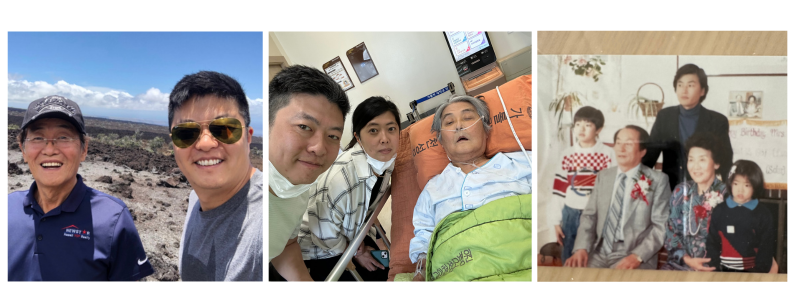

We spent the past seven years in regular and positive contact. Several years ago I visited him in Hawaii and two years ago in Korea.

To some extent we became friends. We’d talk about the NBA, my dating life, the occasional existential topic. I was grateful for these conversations. We didn’t have a language barrier like so many other Korean-American families. We were willing to reconnect after being estranged for so long.

When he passed, I found myself doing something I hadn’t done in many years:

Grieving things that never happened.

Years ago I grieved the family life I thought I’d have. With my father, it was grieving the relationship I wished for and the one we will now never have, despite our recent gains.

One of the last things I said to him was, “You’re young, Dad. You’re only 76. Grandpa was 96 when he passed. You’re going to leave before I’m even 50. I asked you to stop smoking so many times.”

I couldn’t believe those words came out of my mouth. It felt like the 6-year-old boy in me finally got to let something out, it just came through the body of a 46-year-old man. My father, half-paralyzed from a stroke and unable to talk, responded through tears.

I’m grateful we had that moment and disappointed we won’t get to build on it. There are plenty of friends I can talk with about sports, women, and the meaning of life. What I wanted was a father. Intellectually, I always knew that. After his passing, I felt it.

And when I allow myself to, I admit that I miss him.

Though it’s only been a few weeks, his death helped me understand many things about myself:

- Why I built an impenetrable, guarded life.

- Why I battled low self-esteem.

- Why I clung so tightly to church in my youth.

- Why I feel allergic to big emotions and overly emotional people.

- Why I overwork.

If there’s one thing that’s made me effective at work, it’s understanding this: everyone’s problems are important to them, even if those problems sit differently on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

My “lifequakes” aren’t necessarily worse than anyone else’s. I’ve never been bombed, had a loved one murdered, or been given a terminal diagnosis. But there’s rarely any compassion in comparison. It’s okay to validate your own struggles. You don’t have to justify your pain to feel it.

Professionally, I’ve done a few things worth noting. But zooming out, it’s clear much of my success was fueled by fear and pain. I succeeded so I’d feel safe. It was never a goal of mine to be ambitious or influential. I just wanted a quiet, peaceful life: a pretty wife, two kids, a white picket fence. The kind of life 80’s sitcoms told me was good. Probably all an attempt to make up for the chaotic upbringing I had.

Several years into my marriage, we moved into the town I grew up in. Finally, a chance at redemption! To overwrite the chaos of my youth and build the family life I never had!

Instead, my 12-year marriage ended. I started my life completely over. My business was only six months old at the time. This August my business turns ten. Time flies.

My life looks nothing like I thought it would and maybe yours doesn’t either. I no longer feel the need to resolve that contradiction for myself. I think it’s healthy to grieve what was missing. But you can also spend your whole life grieving what’s missing and miss what’s right in front of you.

I’m still learning what to do with all this and don’t have a neat bow to tie it up with. For now, I write. That feels like a good place to start again.

Perhaps you can start again in your own way, too.